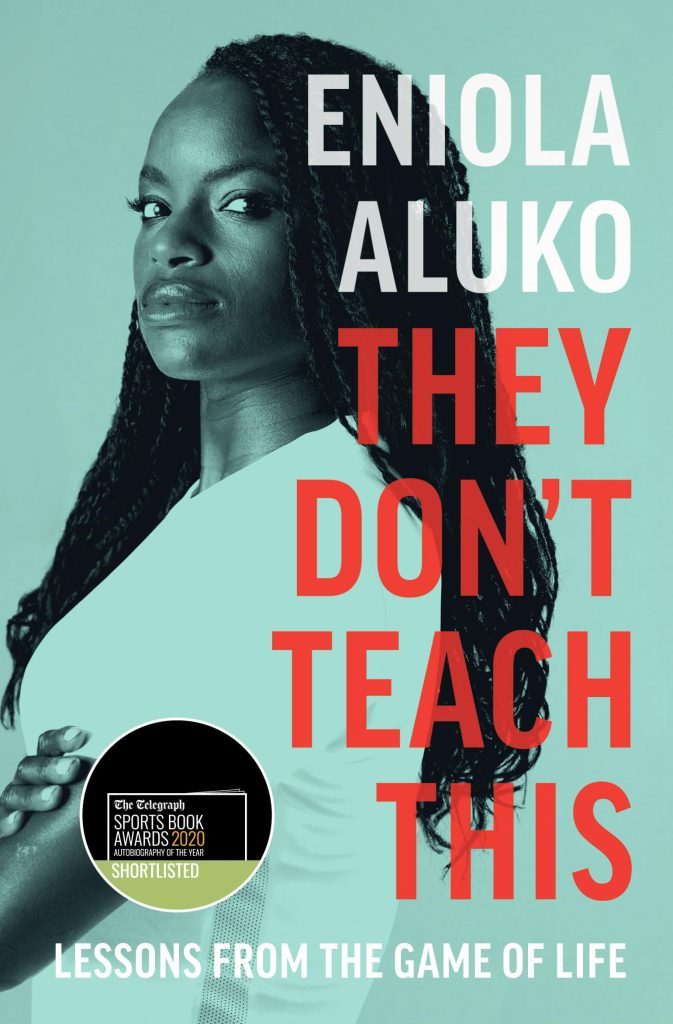

I read They don’t teach this, the autobiography by Eniola Aluko, a while ago, but it stayed with me. Here is why.

I like life stories, and especially those that contain the element of mobility, of functioning in other cultures and possibly some good identity challenges. Eniola has gone through quite a few of these. She was born in Lagos, Nigeria, but her family moved to England when she was just one year old. She will therefore feel like a mixed identity throughout her life. As she herself says:

“And so began a new life for Mum, Sone and me, a life that would see me raised with one foot in two countries. It was an upbringing that gave me a hyphenated identity. I would be neither solely British, nor solely Nigerian. I would be both, I would be British-Nigerian. It was a balancing act; one I would spend my whole life learning how to navigate” (They don’t teach this, pg. 61)

The incredible power of this autobiographical story lies precisely in this duality of identity, which forces Eniola to constantly adapt to different situations. Her English identity does not understand why it must not be revealed to the extended Nigerian family that the girl has a passion for football and spends the afternoons after school kicking the ball with her peers in the neighbourhood. The same behaviour in her brother Sone (who also became a famous footballer) is admitted and encouraged, but in her case it is different.

Different, moreover, is the treatment that she receives at certain moments of her brilliant football career, and only because of her Nigerian identity. Eniola dwells on some of these at length, sometimes giving the impression of using the story to vent the bitterness that certain attitudes have caused her. For example, she recounts how the goalkeeping coach, after England’s victory over Finland (a match in which Aluko had also scored a goal), had called her “as lazy as fuck”. Behind her back, because Eniola had become aware of the criticism by watching the recording of the match.

Instead, she had received a racist comment directly in her face from the then England coach, Mark Sampson. England was about to face Germany, a big event that many friends and family of the players would also be attending. When Enola informed the coach that her family would be arriving from Nigeria for the match, he told her to make sure “they didn’t bring Ebola”

Naturally, all these facts were not ignored. Indeed, sometimes one gets the impression that the book is Eniola’s supreme clarifying gesture towards a world that should promote values of sisterhood, solidarity, honest competitiveness, and is instead pervaded by racism, discrimination and silence.

Yes, even silence because the first investigation – Eniola always says – had resulted in the cover-up of the whole affair. Another moment of great bitterness and frustration for the young player, whom, however, does not let herself be discouraged.

What emerges from Eniola Aluko’s book is a determined and lucid woman. Pervaded by a very deep faith that supports her and accompanies her even in the darkest moments, Eniola does not close herself to a single profession, but while she climbs the peak of her football career, she graduates in law and begins to collaborate with big names in law firms.

Success, willpower, discrimination, faith, and strong family ties are the ingredients of Eniola’s young life, which she mixes and faces wisely, with a determination that can sometimes seem a bit extreme, but that certainly contributes to making us live, even just for the duration of the reading, in a skin and origin different from those that dominate in many environments, and, sadly, also in the football field.

Eniola dedicates the final part of the story to her Italian period, with Juventus. It is a somewhat hasty chapter, in which in my opinion she does not sufficiently delve into the reasons that pushed her to terminate her contract before its expiration and return to England. Even if the few episodes of racism that she narrates could be enough to make us understand that for people “different” from the masses, the search for an environment where one’s skin stops being a distinctive and branding element, must be a constant in life. A tiring and unjust constant.

Luckily, there are women like Eniola Aluko who have a voice, and they use this voice loud and clear, and they fight for a fair, just world where all human beings can live and work in full equality – in all environments, including football.